Recent analysis by the BBC has revealed that burning household waste in large incinerators has become the dirtiest method of electricity generation in the UK. Approximately half of the rubbish produced in UK homes, including a rising quantity of plastic, is now incinerated, prompting scientists to label this trend a “disaster for the climate.” Calls for a ban on new incinerators are increasing as concerns about their environmental impact grow.

The BBC’s investigation, which spanned five years of data, highlighted that incineration emits greenhouse gases comparable to those generated by coal power— a fuel source the UK phased out last month. The Environmental Services Association, representing waste management firms, has contested these findings, stating that emissions related to waste disposal are inherently difficult to manage.

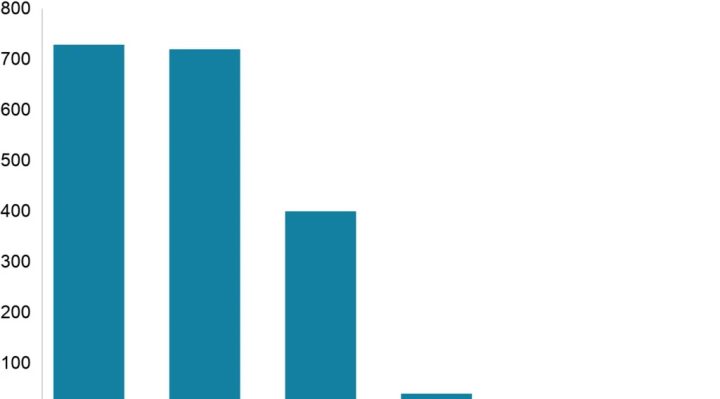

The UK government has been increasingly alarmed by the greenhouse gases produced from landfill waste and its contribution to climate change, leading to a significant tax increase on councils for burying waste. This financial burden prompted many local authorities to turn to energy-from-waste plants—incinerators that convert waste into electricity. Consequently, the number of incinerators in England surged from 38 to 52 within five years.

While incineration reduces harmful greenhouse gas emissions from food waste, the same cannot be said for plastic waste. Being derived from fossil fuels, the burning of plastic generates substantial levels of greenhouse gases. Recent years have seen a shift, with more plastic waste being incinerated and less food waste being sent to energy recovery, as councils now direct organic waste to anaerobic digesters or composting facilities. However, government estimates continue to reflect outdated data, assuming waste composition has remained unchanged since 2017.

The BBC’s analysis employed data on actual pollution levels from incinerators, revealing that energy-from-waste facilities now produce greenhouse gas emissions on par with coal burning. This alarming finding comes as the UK seeks to eliminate carbon emissions from electricity generation by 2030, leaving incineration as the country’s most polluting energy source. Currently, energy generated from waste is five times more polluting than the average UK electricity unit.

Despite incinerators contributing to just 3.1% of the UK’s energy supply, the UK Climate Change Committee warns that their role in emissions will likely grow. Dr. Ian Williams, a professor at the University of Southampton, described the reliance on incineration as “insane,” emphasizing that it contradicts efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Lord Deben, the Conservative environment minister who initiated the landfill tax in 1996, expressed concerns over the increasing number of incinerators, stating that the proliferation of such facilities undermines recycling efforts. Nonetheless, new incinerator projects continue to be approved; a recent £150 million site in Dorset was greenlighted by the UK government, despite local opposition that argued it would hinder the county’s net-zero emissions goals by 2050.

In contrast, Wales and Scotland have enacted bans on new incinerators due to environmental concerns, with growing calls from academics and environmental organizations for England and Northern Ireland to follow suit. The UK Climate Change Committee has advocated for the cessation of new plant constructions unless there are measures in place to capture all carbon emissions. Currently, only four out of 58 UK incinerators have plans to capture emissions, with a single pilot project in operation that captures merely one tonne of CO2 annually, despite emitting over half a million tonnes.

As incinerator usage is expected to rise, existing facilities are increasing their capacity without undergoing new permit processes, circumventing public consultation. Data indicates that nearly half of the UK’s incinerators have secured capacity increases approved by the Environment Agency.

The composition of waste being incinerated is also shifting, with local government data showing an uptick in plastic waste, the most environmentally damaging type to burn. Government statistics reveal that burning plastic emits 175 times more CO2 than landfilling it.

Experts like Prof. Keith Bell of the UK Climate Change Committee have cautioned against continuing the current trajectory. He emphasized that achieving clean power by 2030 cannot be reconciled with an increased reliance on waste burning.

Although a temporary ban on permits for new incinerators was enacted by the previous government while reviewing waste burning policies, it was not extended when it lapsed in May. The current government’s stance remains unclear; senior civil servants at the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero stated they would withhold approval for a proposed incinerator in North Lincolnshire until the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) clarifies its policy on waste incineration.

Local councils face significant challenges in shifting away from incineration due to long-term contracts with waste operators, amounting to approximately £30 billion. These contracts, some lasting over 20 years, have been criticized for locking councils into financially burdensome commitments, limiting their ability to explore more sustainable waste management solutions.

Recent Freedom of Information requests revealed that numerous councils have contractual clauses mandating minimum waste deliveries to incinerators, a practice referred to as “deliver or pay.” This restrictive approach has resulted in financial penalties for councils that fail to meet waste delivery targets.

In response to stagnating recycling rates, which have remained at about 41% in England over the past decade, local authorities are calling for contracts that allow them to reduce waste sent to incineration while boosting recycling efforts. The Local Government Association has raised concerns about how existing contracts hinder environmental progress.

The Environmental Services Association maintains that incineration complements recycling efforts, attributing stagnant recycling rates to inadequate recycling policies. Defra has reiterated its commitment to reducing waste and fostering a circular economy that emphasizes reuse, reduction, and recycling.

Conclusion

The analysis of incineration practices in the UK raises critical questions about the sustainability of current waste management strategies. As the nation strives to meet ambitious carbon reduction targets, addressing the environmental implications of waste incineration must become a priority to avoid locking into practices that could exacerbate climate change.